Blog |

Where Rice, Mangroves and Dikes Connect in Guinea-Bissau

A look at the relationship between protecting and restoring mangroves and rice cultivation.

Guinea-Bissau is a mangrove country. Mangrove forests presently cover some 326,000 hectare – 9% of the national territory, the highest proportion in the world. While still substantial in size, the total area of mangrove forests in Guinea Bissau has actually declined by 32% over the past 80 years. The evolution of the country’s mangrove forests reflects the history of agricultural expansion and use, in particular, rice cultivation in areas formerly covered by mangroves – a practice that reached its peak in the early 2000s and then showed a gradual decline thereafter.

Mangrove rice cultivation involves building earthen dikes to protect the rice fields from seawater ingress. This labor-intensive farming requires constant maintenance to maintain and reinforce these dikes. In addition, as the sea level rises with climate change, the sea is increasingly likely to overtop the dikes and destroy the crops unless there is a sufficient barrier of mangroves at the water’s edge.

With changes in rainfall patterns, and an exodus of young people to urban centres, farmers are finding it increasingly difficult to maintain the dikes on the edges of their fields and have been forced to abandon many rice fields.

If the old, breeched dikes are kept in place on the margins of the abandoned rice fields, the tide may not penetrate sufficiently into the formerly cultivated areas to encourage the natural restoration of mangroves, and the soil becomes prohibitively salty and acidic. In this situation, both farmers and the environment lose out. A Global Environment Fund project called The Restoration Initiative (TRI) in Guinea-Bissau aims to reverse this trend by strengthening food security on the one hand and restoring the mangroves on the other.

To this end, the project aims to support communities in the rehabilitation of rice fields that they consider the most essential to their security by providing them with the means to reinforce dykes and improve hydraulic management of cultivated areas. In return, the villagers commit to flattening the upper part of the dikes of abandoned rice fields to allow the sea, and mangrove seedlings (called propagules), to enter again and thus promote a natural restoration of the mangroves.

On part of the project's intervention sites, rice fields are threatened because they do not benefit from a sufficient mangrove margin to protect the dikes from the effects of marine erosion (photo below). In order to restore this protection, it is necessary to regain space on the threatened rice fields to plant mangroves.

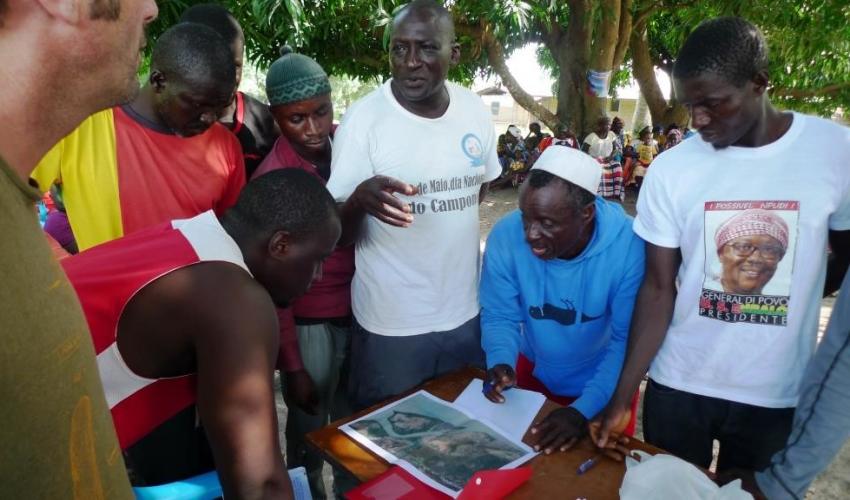

All these situations of strategic retreat imply a high level of requirement in terms of territorial diagnosis, consultation, negotiation and implementation of solutions. Following several identification missions, the project is currently in a phase of territorial diagnosis carried out with the participation of the communities.

The situation of rice fields and mangroves is analysed during field visits coupled with aerial images taken by drone. During these visits, farmers provide a set of information on the evolution of their territory and the solutions they recommend for the future. These solutions are then discussed and evaluated on a technical and financial level before any decision is taken. In the coming months formal agreements will be signed by the stakeholders before the work on rice field rehabilitation and mangrove restoration can begin.

Compared to other rice field rehabilitation projects in Guinea-Bissau, the TRI project is characterised by an ecosystem focused participatory approach that takes into consideration the issue of mangroves and climate change, exploring nature-based solutions with a view to restoration. These solutions will be systematised and shared for possible replication at the national level. In addition, a draft law on mangrove conservation will be developed with the support of the TRI project.

—Web story by Pierre Campredon, TRI project Technical Advisor, Institute of Biodiversity and Protected Areas of Guinea-Bissau (IBAP) and Rui Andrade, Project Coordinator, IBAP

Note: The participatory territorial diagnostic was undertaken collaboratively by en Haut!, IBAP and IUCN.